People often say, “Come on, it is not rocket science.” The irony is that the first person who really explained context switching to me actually was a rocket scientist. His name was Andy Mather, a developer I worked with at Rippleffect.

It started as a casual chat about processors and how they seem to multitask. That quickly expanded into a much bigger conversation during a train journey we were on together, heading down to meet the British Horse Racing Association. Andy explained how even computers are not really multitasking. A single core executes one instruction at a time. What looks like multitasking is just extremely fast sequencing. Modern processors get around this by adding multiple cores and using techniques like hyper-threading, which create the effect of parallelism. But even then, each core is still focused on one instruction at a time. By the time we arrived, I was seeing my own working day in a new light.

We have all heard about multitasking. The idea that you can juggle two or more things simultaneously. But the reality is not that neat. Every time you switch tasks, every context change, there is an overhead. Sometimes it comes from other people pulling you away. Sometimes it comes from your own decision to spin too many plates at once because it feels like you are being more productive. Either way, the cost is the same.

This has been discussed at length in programming circles. Joel Spolsky’s blog post Human Task Switches Considered Harmful is still a classic, but I do not see it talked about as much elsewhere. Yet the impact is universal.

…once you establish that culture, interruptions drop, people grow, and managers regain the time to focus on high-value work.

Why empowerment and self-discipline matter

This problem is not unique to one sector. I have seen it in software development, project management, fintech, legal and media. And it does not just affect one layer of those organisations. It touches everyone, from engineers and analysts through to consultants and lawyers.

The pattern is consistent. Talented people are pulled out of focus because their teams do not feel able to move forward without permission. But there is another angle too. Even when nobody is interrupting, people often decide to take on two things at once. It feels productive in the moment, but it is just as damaging. Switching between tasks by choice still carries the same overhead, and the result is the same: less progress on the work that matters.

I was speaking with an IP solicitor in London who realised this after a conversation we had. His staff were constantly asking him to make small decisions. The questions were not bad ones, but they reflected a learned behaviour. They had come from environments where command and control was the norm, so they defaulted to seeking approval rather than solving problems themselves.

It is when you move into management that both challenges become most obvious. The interruptions multiply, and the temptation to multitask grows. Empowerment is about freeing people to move forward without constant approval. Self-discipline is about resisting the urge to jump between tasks just to feel busy. Both are critical if you want to protect focus and deliver meaningful work.

The exceptions to the rule

Of course, there are times when switching makes sense. If you have ever used the “eat the frog” approach, tackling the hardest task first, sometimes you need to switch briefly to something lighter to recharge.

Occasionally, a genuinely time-sensitive issue crops up where the short-term cost of a switch is outweighed by the long-term pain of ignoring it. And sometimes tasks are naturally sequential. You hand something over to design, legal, or testing, and you pick up the next item while it is parked.

But these should be exceptions. Every day context switching, whether caused by interruptions or by your own choices, is where productivity goes to die.

But computers multitask, why can’t we?

People sometimes push back and say, “But computers multitask, why can’t we?” I always think back to that train conversation with Andy. Even computers are not really multitasking, and unlike us, they do not have emotions in the mix.

So what do you do?

On paper, it is simple:

• Keep a clear list of tasks, ordered by value.

• Work through them sequentially.

• Do not be seduced by shiny new distractions unless they are a true priority.

This is what the most effective managers and programmers do. They get work finished, not half done. Delegate where possible, and focus energy where it has the most impact.

Because if you keep switching between tasks, whether it is caused by other people or by yourself, you do not get one hundred percent of anything. You get fifty percent of two things. And whether it is a client or your wife, neither will thank you for that.

How to reduce interruptions

The other half of the challenge is managing the context switches created by others. This is where empowerment matters. If people feel they cannot move forward without your permission, your day will fill up with small interruptions that chip away at your focus.

The way to reduce this is to deliberately coach your team to take ownership. That means:

• Making it clear which decisions they can make without you.

• Creating safe spaces where mistakes are treated as learning opportunities, not failures.

• Encouraging people to prioritise before they escalate.

Empowerment does not happen instantly. It is a skill that has to be practised, both by leaders who need to let go and by teams who need to build confidence in their judgment. But once you establish that culture, interruptions drop, people grow, and managers regain the time to focus on high-value work.

Instead of a vicious circle, it created a positive cycle where focus led to delivery, and delivery built the confidence to focus.

My approach

When I work with teams, I focus on spotting these patterns early. If I see constant interruptions, bottlenecks, or hesitation in decision-making, it usually signals a lack of empowerment. If I see people spreading themselves too thin, it usually signals a lack of self discipline or clarity in priorities. Rather than criticise, I coach people through it. We talk openly about what decisions they feel comfortable making, where they need more support, and how we can build psychological safety so they are not afraid to try, fail and learn.

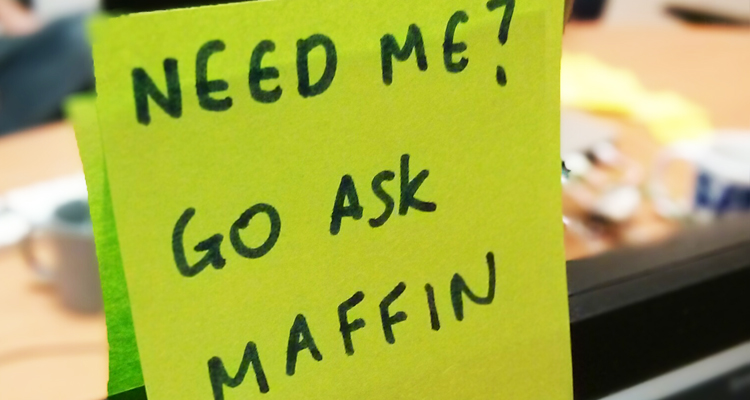

One developer I worked with took an amusingly direct approach. He was so focused on finishing a high-value piece of work that he stuck a Post-it note to his screen which simply read “Ask Maffin.” That way, anyone approaching him knew he was in the zone and the question would be redirected to me. It was funny, but it also highlighted a bigger issue. While it meant he could power through and deliver, it showed how much overhead interruptions create and how important it is to educate people on prioritisation and on setting the right times to ask questions.

As I dug further, I realised these interruptions were often coming from account managers, the people dealing with clients day to day. The reason they felt the need to panic and ask for instant answers was twofold. First, a culture had been set by senior authority figures that rewarded immediacy over considered responses. Second, clients themselves had learned that if they asked, they would get something back right away, even if the issue was relatively minor.

Surfacing this let me get to the root of the issue. It allowed me to work with the business to reset expectations, coach account managers on prioritisation, and encourage a healthier balance between responsiveness and focus. By tackling the cause rather than the symptom, the company began to change the culture, and developers could focus on delivering the work that mattered most. This in turn meant more work was completed and interruptions reduced. Instead of a vicious circle, it created a positive cycle where focus led to delivery, and delivery built the confidence to focus.

This is not a one-off conversation. It is a habit that gets built over time. The goal is to move from a culture of command and control to one where people feel trusted to act, and leaders can step back to focus on higher value work. I make it clear that leadership skills and self discipline do not magically appear the day you get promoted. They have to be actively developed, just like any technical skill.

That is why I put emphasis on coaching, creating space for people to practise decision-making, and reinforcing positive behaviours. The result is not only stronger teams but also leaders who are less stressed and more focused.

Further reading

If you are curious, Joel Spolsky’s original piece Human Task Switches Considered Harmful is still worth a read. I just wanted to share how it plays out in real projects, teams, and leadership.

“I worked with Ben for almost three years in his role as the Lead Scrum Master role at Lendscape. During this time Ben was a senior member of the management team that successfully delivered Lendscape’s first major Asset Finance client, a pivotal step in the company’s growth strategy.” – Matt Smith, Delivery Director, Lendscape

Latest Delivery Posts…

A selection of blog posts relating to delivery and how to get projects over the line…